Executing the Bucket Monsters

25 years ago (minus a few days), Lotfy Khalil was born in the Shenou district outside of the city of Kafr el Sheikh. I haven’t met him, and the chances of meeting him in the future are almost nil since, as of June 19, the Supreme Court for Military Appeals has upheld a death sentence against him. The same verdict also befell six other people — three of which are detained with Lotfy — charged in relation to the April 2015 Kafr el Sheikh stadium bombing that killed three military college students.

Of those sentenced to death in connection to the case, Lotfy is the youngest. According to his parents, he also disappeared longer than the rest of the detainees after his arrest; they didn’t know anything about his condition or his whereabouts for 76 days.

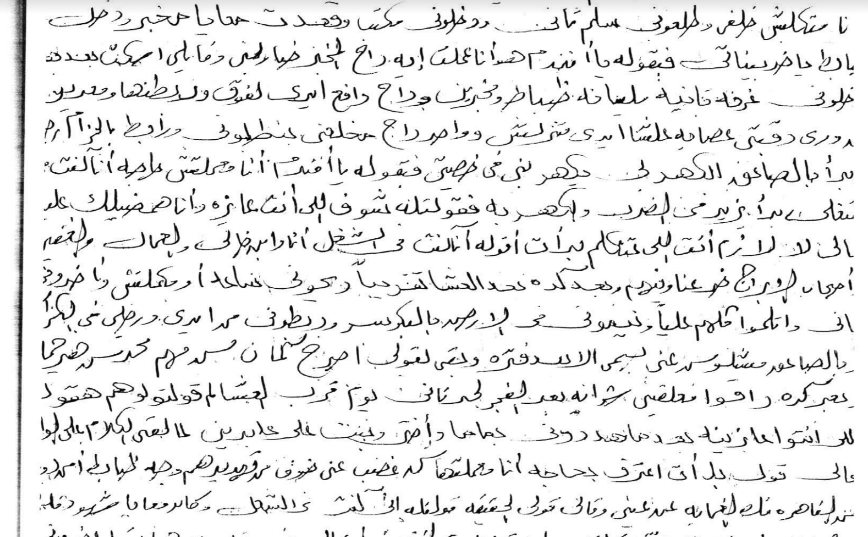

When they were finally able to see him, Lotfy handed his mother a letter detailing what he had endured for over two months. In this letter, a fragment of which is shown in his handwriting below, he describes officers tying his hands to a pole above his head and maintaining them by a stick behind his neck, removing his pants and tying his feet together using his belt, electrocuting his testicles, and beating him more (and more frequently) whenever he asks why he is being tortured. “Okay, I will sign whatever you want me to confess to..”

Why are they doing this to our children?

That was the question Lotfy’s mother asked me after his death sentence was upheld. I know she wasn’t asking me for an answer, but I was still disturbed by my silence and my inability to respond. Really, why are they?

The first possible answer: Because they deserve it. Because “whoever kills shall be killed” is custom, and when someone commits premeditated murder, they give up their right to live. Pushing all philosophical dialogue aside — because exploring the different arguments of philosophy schools would need a much larger space than this — the problem with this line of argument is that it stops as soon as one perpetrator, the first perpetrator, is identified. So the idea of the state’s killer becomes absurd. But aren’t those who carry out death sentences committing murder? Aren’t all executors of death sentences killers? Aren’t the institutions ordering the death of individuals also murderers? Can these same institutions order the rape of a rapist, for example? Or robbing a thief? And why does the judge, announcing the verdict, say “execution” by hanging, and not “killing” by hanging?

“Because he did so and so.” This answer is always delivered with a tremendous amount of unexplainable confidence. How, if ever, can someone be sure that one particular individual committed the crime(s) they’re accused of?

In the case concerning Lotfy and his peers, official documents carrying the state’s official stamp and signed by a number of officials contain a detailed description by Lotfy, Ahmed, Sameh, and “Uncle” Ahmed, as Lotfy’s younger sister refers to him, of them being tortured and threatened to say certain things in front of the prosecution.

Even when they met with the prosecution (in most cases a “fictional prosecution”) and narrated what they had been subjected to, they were again suspended and electrocuted, among other sickening methods of torture, until they were forced to confess to their involvement in the 2015 bombing by attaching a remote detonator to a motorcycle. Afterwards, technical reports written up by experts indicated that the remote detonator was attached to a phone, parts of which they found in the debris, proving beyond doubt that the phone, and not “a motorcycle remote detonator,” set off the explosion. The reports also stated that the bomb was placed in a military school student’s bag and not “in a plastic bag,” as Lotfy and the rest of the detainees had mentioned in their admission of guilt.

Sworn witnesses, whose testimonies are included in the official documents, place the detainees in places far from the incident during the detonation: Sameh in 6 October City, Lotfy in a different district two kilometers away from the stadium, and Uncle Ahmed 10 kilometers away.

Yet somehow, the court is certain that these four detainees are behind the bombing. The grand mufti himself was sure enough of this to back the court’s ruling, symbolically blessing the killing of four men, and the Supreme Court confident enough to uphold the verdict. Is it possible that the first court fell short? Or that the mufti is mistaken? As a matter of fact, it’s very possible that they all were, including the Supreme Court. After the verdict was upheld, someone being questioned in relation to a completely different case confessed to knowing the perpetrator of the Kafr el Sheikh bombing. It wasn’t Lotfy, Ahmed, Sameh, or Uncle Ahmed — his name was Medhat. Shouldn’t this revelation shake the confidence of the verdict, or at least call for the reassessment of the decision to kill four people who could be innocent?

Many other things cast a shadow of doubt over their guilt, such as the security cameras around the stadium, which should have been able to provide evidence of their presence during the time of the incident, but were all impaired by “technical malfunctions” that prevented their use and review in court. Another would be head of the local police admitting that his investigation has “not revealed the perpetrator of the incident.”

All these details could save lives if reviewed and verified.

The defendants’ families submitted a request to have the death sentences put on hold until the case was reviewed, and in 10 days were notified of its rejection. For one reason or another, anything that could and should cast doubt on the certainty of the verdict has been dismissed by the court.

Lotfy continues to write letters to his family. He fills them with hearts and smiley faces - not because he is happy or because his conditions have improved, but because he refuses to give his family more news of his daily suffering. All they know of this is that he receives his food in a bucket, and that he is given a plastic bag to excrete in for 23-and-a-half hours each day, before he gets the chance to empty it during the half-hour he is permitted outside his cell.

In order to entertain the suspicions surrounding the legitimacy of ending a life, one must consider the threatened lives valuable to begin with. Putting aside the debate regarding the viability of the order to kill, it is important to contemplate what this necessitates in term of mentally, physically, and psychologically distancing yourself from those who then become kill-able, and the need to symbolically strip them of their humanity; probably the only thing left which may trigger a sense of commonness or similarity.

We hear nothing from those whose murders are ‘okay,’ but we are told a lot about them - a lot to help us dehumanize them. We are told what monsters they are, and how their monstrosity killed other people more deserving of life. We are constantly initiated to believing that getting rid of them is better for us; that their continued existence — even in a dark cell with no windows — is an imminent threat; that there is no controlling their violence, which is always on the verge of exploding in our faces.

Alright, let’s think of them as real monsters, less human than us and thus more deserving of death. What about our own humanity? In taking the decision to kill, with such ease of mind that allows a comfortable night’s sleep, how similar are we to the monsters that we pretend to be so different from?

These people are not animals to eat out of buckets, or to be sacrificed (anytime other than official holidays, as stipulated in the prison regulation articles) to rid society of evils and dangers. Evil and danger do not lie in those four individuals, neither are they embodied in hundreds of others; on the contrary, evil and danger are reflected in the underestimation and dismissal of human lives: the message that the state, the supposed role model, delivers with every “execution by hanging to death” verdict, and every paper blessing from the mufti, and every bucket and plastic bag and doubt and silence.

The timeline of the Kafr el Sheikh stadium bombing case

- 15 April 2015: A bomb detonates in the waiting area designated for military school students in Kafr el Sheikh Stadium; three students are killed

- 19 April 2015: General prosecution refers the case to the military prosecution

- 19-20 April 2015: Four suspects arrested; their families file forced disappearance reports

- 30 June 2015: Arrest warrants issued for the defendants

- 4 July 2015: Arrest of defendants announced in media

- 1 February 2016: Seven defendants, four of whom are in custody, are sentenced to death; their documents sent to the mufti for approval

- 2 March 2016: The Alexandria military court sentences seven defendants to death

- 26 April 2016: Defense Minister upholds the verdict

- 9 July 2016: Sentence appealed

- 19 July: The supreme court for military appeals upholds the sentence

For more details on the case:

Death Sentences in Kafr al-Sheikh Stadium Case After Unjust Military Trial